Running a successful furniture design school is all about teaching the techniques and skills needed to design and make beautiful furniture.

In a sense, teaching those skills and techniques is the easy part because making basic furniture is something that human beings have been doing for thousands of years.

And, because human beings haven’t changed much over the millennia, the basic forms and shapes of furniture haven’t changed much either.

Skara Brae, a preserved Neolithic hamlet in the Orkney Islands, provides a good example. Without trees to build from, that ancient people used stone – the reason why it’s so well preserved.

What’s amazing about their stone furniture is that they made beds, cupboards, dressers and shelves – everything their homes needed.

Since then, while materials might have changed, the things we need haven’t much changed. We still need chairs or beds.

The more difficult part of teaching furniture design is empowering a student to find an inner creativity that can find expression in their woodwork.

But what I’ve found in over 30 years in teaching woodwork is that most human beings are innately creative, and it usually doesn’t need too much tuition for them to find it again.

I say “again” because it seems to me that the educational curriculum, here and elsewhere, is geared towards teaching creativity out of young people.

They are encouraged to learn maths or languages, chemistry or biology; the subjects that are best suited for progression to higher education or the world of work.

Okay, but only up to a point. I would also like the innocent creativity of childhood to be fostered into adulthood, so that nobody loses the magic of their imaginations.

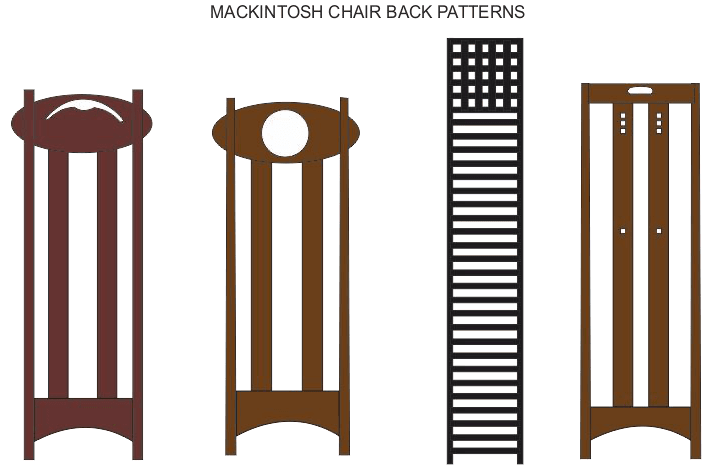

Take some of the great furniture designers of this century and the last – from Charles Rennie Mackintosh to George Nakashima; or from Le Corbusier to Mies van der Rohe.

These are designers who took the art of creativity to new levels, forming new relationships between form and function to produce innovative new designs.

They were also prepared to push established boundaries of style and taste, because their inner imaginations didn’t allow for arbitrary boundaries.

A lot of students arrive at the Chippendale school thinking that they aren’t particularly creative, often simply because they didn’t do well at art at school. Rubbish! is what I tell them.

What I find is that when students unlearn much of what they’ve been taught, their innate creativity comes back to them – a subconscious force that seems to lurk not too far under the surface.

It’s a force of imagination that is able to take inspiration from nature or from reimagining the things that surround us. It’s a freedom of thought that allows us to experiment, get things hopelessly wrong, and then move onto a better thought.

It’s a creative force that lies within us all, and at the Chippendale school we dare to boast that we can unlock yours.

Anselm Fraser, principal, Chippendale International School of Furniture