“What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9)

It’s an apt quote for every furniture designer to remember because, while you may think that your innovative idea for a next-generation chair is revolutionary – chances are it’s been thought of before.

It’s a lesson that we teach our students at the start of each course, because the human body hasn’t changed much over the millennia. Therefore the things we lie on, sit on, store things in, or eat at haven’t changed much either.

Take, for example, the bikini. Designed in France (where else?) and unveiled in Paris in 1946, its name was inspired by a US atomic test on an atoll in the Pacific Ocean. So, not such a romantic name.

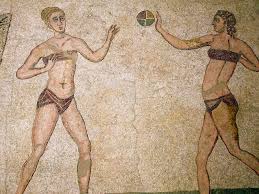

However, despite becoming an icon of post-War emancipation, the earliest surviving depiction of a bikini is on a mosaic found in Sicily and dating from the 4th century AD.

That, incidentally, is the picture in this article, which could easily be in Ibiza or Benidorm. In the intervening sixteen centuries, the bikini hadn’t changed at all.

The same nothing-under-the-sun rule applies to virtually everything else – from the houses we live in to the food we eat. Simply, our everyday lives are shaped by the creativity of centuries.

In furniture design, we need only look to a small Neolithic settlement on Orkney, a stunningly-beautiful island archipelago off the north of Scotland.

The settlement itself is called Skara Brae and consists of eight dwellings, linked together by a series of passages, and dating to between 3200BC and 2200BC.

Remarkably, each house has surviving beds, cupboards, dressers and shelves. The only reason they’ve survived, making them some of the world’s oldest furniture, is that Orkney didn’t (and doesn’t) have trees. All the Stone Age furniture is aptly made entirely from stone.

Maybe not very comfortable, but a salutary lesson that furniture designers have been designing furniture for over 4000 years. Hardly surprising therefore that we’ve ended up with comfortable chairs, beds, tables and chairs – we’ve had many centuries to get the basic designs right.

In other words, as we tell our students, be very careful what you design and then claim to be original. After all, there are thousands of furniture designers out there, all trying to reinvent what has already been invented.

The trouble, of course, is determining if a newly-designed chair really is the unique, innovative and revolutionary piece of furniture that its creator claims – or merely a variant on an existing design.

The difference between innovation and variation can be very small, and open to wide interpretation, but could land an unwary designer in trouble. The internet makes everything visible, across continents.

It wasn’t always so. Take Thomas Chippendale, the revered 18th century designer and maker who has lent his name to the Chippendale International School of Furniture.

He was happy to publish his “Gentleman and Cabinet-Makers Director” – which made him a household name – and which contained every one of his furniture designs, many of which were themselves adaptations of existing styles for a mid-18th century audience.

With the publication of the Director, other furniture makers were able to plagiarise from his designs – at least until the end of the century when they began instead to plagiarise from the French styles of Louis XV and Louis XVI.

Back then, of course, imitation was seen as the sincerest form of flattery. It cemented Chippendale’s name in the lexicon of great furniture designers – and has cemented our name as one of the world’s leading furniture design schools.

Anselm Fraser, Chippendale International School of Furniture