In the first of a series of articles on modern woodworking, Anselm Fraser, principal of the Chippendale International School of Furniture, looks at the 20th century greats, and offers an upbeat assessment for woodworking in the years ahead.

As a furniture design school, our primary focus is to teach woodworking. It’s that fundamental skill that our students can take into their creative and business lives – to design and make beautiful furniture.

But what is beautiful furniture? – and how can you teach someone to be creative? After all, to succeed in furniture design requires skills and talents that few of us possess.

The trick, I believe, is to go back to basics and first understand why some furniture designs have withstood the test of time, and why others have entirely faded from memory.

Until the start of the 20th century, all furniture was made from wood. It was the only available building material – cheap, plentiful and easy to work with.

But wood carried with it one important drawback – production of chairs, tables and beds was limited by the number of craftsmen and women able to fashion a tree into a functional piece of furniture. That made good furniture very expensive.

The Industrial Revolution that had transformed virtually every aspect of manufacturing had entirely bypassed furniture design – the intricate tasks involved in transforming wood into furniture were incapable of being mechanised.

All that changed in the first decades of the 20th century as furniture designers realised that they no longer needed to work with wood – other materials would do just as well, if not better.

It paved the way for mass production, using steel, glass or plastic – and making furniture affordable for everyone. Modernism was born.

Some of those Modernist designs are still classics, while designers such as Walter Gropius, Josef Albers and Charles and Ray Eames remain influential designers for today’s furniture designers.

It’s no coincidence that the likes of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe were also architects, able to balance form and function across disciplines, or Isamu Noguchi, whose classic designs were inspired by his other life as a sculptor.

Their creativity was to move away from wood and to use whatever material best suited their imaginations, or their one blinding flash of brilliance.

For example, Marcel Breuer’s chromium-plated steel Wassily chair was inspired by his bicycle. If a bicycle’s handlebars could be made from tubular steel, he thought to himself, why not a chair?

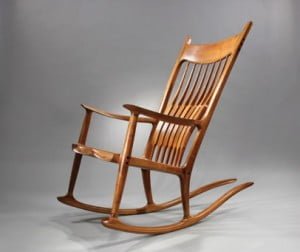

Of course, wood never went out of fashion. It was simply complemented by other materials to make Modernist furniture stackable or practical or affordable. For example, Sam Maloof, the iconic mid-20th century furniture designer, always described himself as being, first and foremost, a woodworker.

His rocking chairs, owned by US presidents and museums, have become collectors’ items for the very rich. One recently sold at auction in Los Angeles for over $80,000 – not bad for a walnut and ebony chair only made in 1986.

The fact is that wood furniture has never gone out of fashion, and my guess is that it’s now gaining in popularity. In the UK, TV advertisements for home furniture have begun to extol the virtues of tables, beds and cabinets made from solid wood.

In an ubiquitous world of cheap MDF and plywood, good old-fashioned wood is being seen again as a material of quality and durability – a simple recognition that, while it may be a bit more expensive, you’re buying something that will last a lifetime.

There’s a bit of psychology involved. Until recently, most of the furniture that we bought came with an unspoken date for its obsolescence. When we changed home, or simply redecorated, we bought new furniture. In the scheme of things, it wasn’t a huge cost – and, anyway, the old stuff was looking a bit tatty.

Now, perhaps after the financial crash, we’ve maybe come to reassess that mindset, because a finely-crafted table, chair, bed or cabinet isn’t simply a fashion statement – it’s something to be treasured over the lifetime, and across generations.

It’s also maybe no coincidence that TV programmes about antiques have become so popular, and not just because we secretly hope that the dreadful painting that Aunt Meg left us is actually a priceless Picasso.

Fact is, we are learning again to treasure the past. And not just the antique things that were made in the past. We are treasuring again the skills and materials from which the past was made – and wanting those things to be recreated today.

That’s why I think that furniture design could be on the brink of a renaissance. Wood is once again being seen as a material to be valued, and furniture no longer unwanted clutter to be chucked away when we paint the living room walls.

In that space between yesterday and today is a huge opportunity for today’s woodworkers and furniture designers: to create pieces that are timeless, able to fit seamlessly into people’s homes – becoming things that will be cherished and passed on to children and grandchildren.

That just leaves the thorny question of creativity, and how to design the next great thing – even if you’re not particularly creative. Oh, and one other small issue: how to price your creation so that people will actually want to buy it.

Those, however, are questions for future articles.