Chippendale School of Furniture’s Anselm Fraser fuses big sky thinking with commercial savvy

Main part of a feature published in Good Woodworking in Growth Rings in October 2011. Reproduced with thanks. Words: Darren Loucaides. Photos: Dave Roberts.

As mist settles on the hills surrounding this secluded spot in Gifford, 25 miles east of Edinburgh, it feels like we’ve happened upon a deserted country house. Chippendale International School of Furniture is out for summer, and stalking around its exhibition hall, quiet but for our footfall thundering across the rugged floorboards, the atmosphere is eerie. Perhaps we’re hearing distant echoes, glimpses of movement just beyond our vision – hints of the life that usually fills the place.

The various wooden creations, like stage props solemnly awaiting their moment in the limelight, only add to the feeling: there’s an Art Deco dressing table, an unfinished rocking horse, a solid all-burr dining table, and a grand chair you’d expect to find nestled deep within the boughs of a magical forest (but is actually destined for the Edinburgh Book Festival). You wonder what kind of curriculum could spawn such an eclectic mix of furniture.

The answer lies with Anselm Fraser, Chippendale’s Principal and founder, who appears before us like the house’s enigmatic phantom. He’s wearing odd boots – one blue, the other gold – and string braces decorated with metal leaves, which provide a handy ‘in’ for understanding the man: on the one hand, they’re a symptom of someone who doesn’t mind being thought eccentric; on the other hand, they’re a marketing tool that easily identifies him. All the people we’ll meet over the coming months during our northern adventures will recognise Anselm – “You know, the chap with the blue and gold boots, and the funny braces” – and have heard something of his distinctive approach. He’s a showman and an entrepreneur, a craftsman and a pragmatist.

You can read The Strategy of Creativity from Good Woodworking here.

This unique mix – Anselm’s very spirit – lies at the very heart of the School. For £16,950 it provides an intense 30-week crash course in furniture making, but also commercial nous: “This is a business school,” Anselm says, “not just a furniture school.” And yet, as is evidenced by the work all around us, the students are also receiving a potent creative stimulus. This is a place for big sky-thinking inspired by the wide horizons of the location

itself…an idyllic base from which to plot your next move.

Oil rigger, egg trader, woodworker

It was a bit of big-sky thinking, fused with realpolitik, that led Anselm to purchase these former Myreside farmsteads for £100,000 back in 1992. He’d realised that, instead of breaking the bank buying a listed building that would serve as a country home and furniture school, he could fashion his own for a much better price.

Before this, though, Anselm had tried his hand at a number of occupations, ranging from a stint in the North Sea on the Brent Delta oil rig to egg marketing in the East Midlands. It was his dairy enterprise that revealed his knack for business: he managed to reduce his storage overheads to almost nothing by seeking out farmers with empty outbuildings. It wasn’t long, however, before the big boys were on to him: a national supplier waged a price war and eventually ran him out of town, but during his two years of trading, he’d generated enough capital for his next venture.

“With the next business,” Anselm explains, “I decided that I didn’t want to make a huge profit: that’s when people come after you, and I’m never going to let that happen again.” He turned his hand to woodworking, partly because, “it’s what I’d always wanted to do,” and partly because it’s difficult to make a living as a woodworker: “I was confident I wasn’t going to be wiped out by a rival, either. After 30 years this has proved to be true.”

He trained with antique furniture restorer Michael Hay-Will for one year, after which, “Off I went with my chisel and my brain,” and started his own business. Initially he concentrated on restoring, but as the market shrank, he started making furniture too. When Michael, his former tutor, died, another avenue presented itself to Anselm – teaching: “His wife simply said, ‘We have a student, can you help?’” Anselm agreed, and from this unexpected acorn grew the Anselm Fraser School of Antique Furniture Restoration, which would later evolve into the Myreside School of Furniture as Anselm began to focus more on furniture making.

Build it…

It was years before the school became a main priority, however; apart from furniture, Anselm was diversifying into property renovation and building projects. He would, and still does, cast his keen eye around for decrepit buildings to pounce on, which he’ll completely overhaul into grand houses like his own. He’s been making swoops far beyond the UK, too, with recent trips to Switzerland to work on wood cabins, and even building a school in Malawi.

You can see the imagination that he brings to this kind of work if you look at his own house. We find his woodwork covering almost every square inch. It’s neither conventional in an interior design sense, nor perfect from a

cabinetmaking point of view, but it’s full of character and charming idiosyncrasy. A house, he’s saying, isn’t just a house but a canvas for experimentation. Apart from the reverse moulds, he made faux stonework from

concrete for the doors, windows, and balustrades, made the floors from local timber that would’ve gone for firewood; there’s furniture made in the round; the kitchen reminds us of Bilbo Baggins’ Bag End (only rather bigger); there’s his ‘Harry Potter’ bed largely made from bark-on branches… “There’s one of my paintings,” he says, pointing at a canvas with steam-bent strips bursting out of it, or, elsewhere, a framed explosion of off-cuts

and paint. It’s all slightly bonkers, but it makes for a wonderfully experimental atmosphere.

This former farmstead, then, has evolved into a kind of creative outpost which now attracts students from around the globe looking to cross the boundaries of a typical woodwork course. This hasn’t happened over night, though.

…and they will come

By 2000, the house was for all intents and purposes ‘complete’, and Anselm was ready to expand after 15 years of training people on a more ad hoc basis. His first step was to find out whether he could rename it the Chippendale International School of Furniture.

“I spoke to the lawyers,” he says, “and they asked if I had international students, which I did,” and, with no copyright on the name, he went for it. The rebranding exercise has certainly helped Anselm in his efforts to build up the School and its reputation in recent years.

The school only took on five to 10 students while it found its feet, he explains, but now it’s reached critical mass with 20 students and 10 ‘incubators’ – former students who’ve stayed on to rent workshop space. He was also fully subscribed for next year back in May. Anselm doesn’t want it to expand any further, though, as the current size allows him to impart a healthy amount of his peculiar wisdom to each student. And keeping the numbers will mean that plenty of the students can continue to stay on as incubators.

What’s the magic formula, then, that has made the School so popular? It’s the two pronged approach, as we said at the start, of providing both making and business skills.

Building a craftsman

The course is 30 weeks long, and leaves students with a furniture making qualification and cabinet making qualification recognised by the Scottish Education Authority. “For the first two terms we have five tutors looking over 20 students,” says Anselm. “We work through a syllabus [approved by the SEA], and they’re taught to work to time tests.” He firmly believes that pushing students to work quickly is fundamental: “The trouble with setting up a business because you love woodwork is that you’re never going to make any money,” he argues. This isn’t to say that students are rushed along before they’re ready: “The biggest challenge is the first two weeks of the course,” he explains. “During this time you have to make them go slow like a tortoise; if you go fast like a hare, you have accidents.”

The students make a minimum of three pieces, including a traditional piece and a modern piece, though they are strongly encouraged to produce more.

“Quite early on, we get them to design something of their own,” Anselm says. “We want them to be great designers, and we think carefully about how to develop and expand them towards that aim.”

Business and pleasure

But alongside this practical course is that dynamic guidance given on how to make a living after the course.

“We teach them not to drop their old skills,” says Anselm, who believes it’s crucial that you utilise the full spectrum of your abilities, not just your woodworking talents.

“To make a living as a furniture maker, it’s going to be very lean for the first few years,” he says. “Don’t throw away your talents. Don’t come to me and say you’re only going to do furniture; you’ll starve…”

If you’re a taxi driver, for instance, Anselm will insist that you keep working your busiest hours and fit your woodworking into the quiet times, at least while you get started. “If you have no other talents, we’ll find something for you!”

His favourite word of advice is “diversify”: aside from using skills accumulated before coming here, he steers them towards other woodwork like restoration and house refits, like he does. The idea is to take pleasure in your making — “That’s why you go into woodwork,” Anselm says, “because you want to enjoy your work” — but to keep several streams of income going.

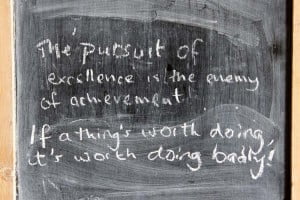

With such a head for business, it’s perhaps not surprising that Anselm feels embattled by some of the attitudes in the fine woodworking world: learning how to sharpen tools to within a thousanth of a millimetre, say, or perfecting seamless joints may be appealing, but they’ll probably lead you into financial ruin if you’re not careful.

“Have gaps in your dovetails!” Anselm cries. “They’re good to see,” which may seem like an odd thing to say, but the essential point carries weight: it’s far better to survive and create exciting furniture to a decent standard

than to risk everything in the so-called pursuit of excellence.

A way of thinking

When students pay £16,950 for a 30-week course, then, they’re buying into a way of thinking through Anselm. It’s his philosophy and character that make this much more than a furniture making school. Chippendale is a centre of craftsmanship and business sense, but also a breeding ground for ideas; a space within which to grow the confidence and ambition needed to be truly creative, but from where you can see the bigger picture, too. No wonder so many of the graduates are keen to rent space and join the Chippendale Incubation Centre unit: apart from securing access to well-maintained machinery and avoiding start-up costs, not to mention benefiting from the big sky thinking of this shared environment, they’ll continue to draw from the fountain of inspiration that is Anselm Fraser and his School.

The mist is lifting now, and we’re able to gaze out over the countryside and far into the distance. There’s an air of quiet before the storm: the workshops are relatively empty, stocked with a few students who’ve been allowed to finish their courses over the summer, tutors working on projects and preparing for the new year, and, of course, the incubators starting their new businesses. But by the time you’re reading this, Chippendale will be growing the latest crop of students, and it’ll be ‘all systems go’ again. Many of them will struggle at first to keep up with the pace and intensity of the course, but in passing on making skills and plenty of commercial savvy, Anselm’s curriculum amounts to a strategy for lasting creativity. Once they finish, after all, the next move is theirs, and they’ll need to call upon all their guile and tactics to succeed.